This article was written by jdmills16 and edited by TheCobraSlayer and Aene of the MAL Articles Club.

Interested in writing or editing for us? Click here!

With its massive and diverse repertoire of styles, it’s certainly difficult to call out any single attribute that is characteristic of all anime. And yet, there are things that viewers have come to expect from these shows, many of which can be ascertained from a brief glance at the title art. When I look at an image of Naruto, for example, I know that I’m about to witness a plethora of trials and triumphs, a tribute to the hard-won victory of the story’s shounen hero. When I glance at a picture of Itazura no Kiss, I expect to see a shoujo romance about the struggles and successes of hard-won love, a tribute to the growth and development of its characters’ self-awareness.

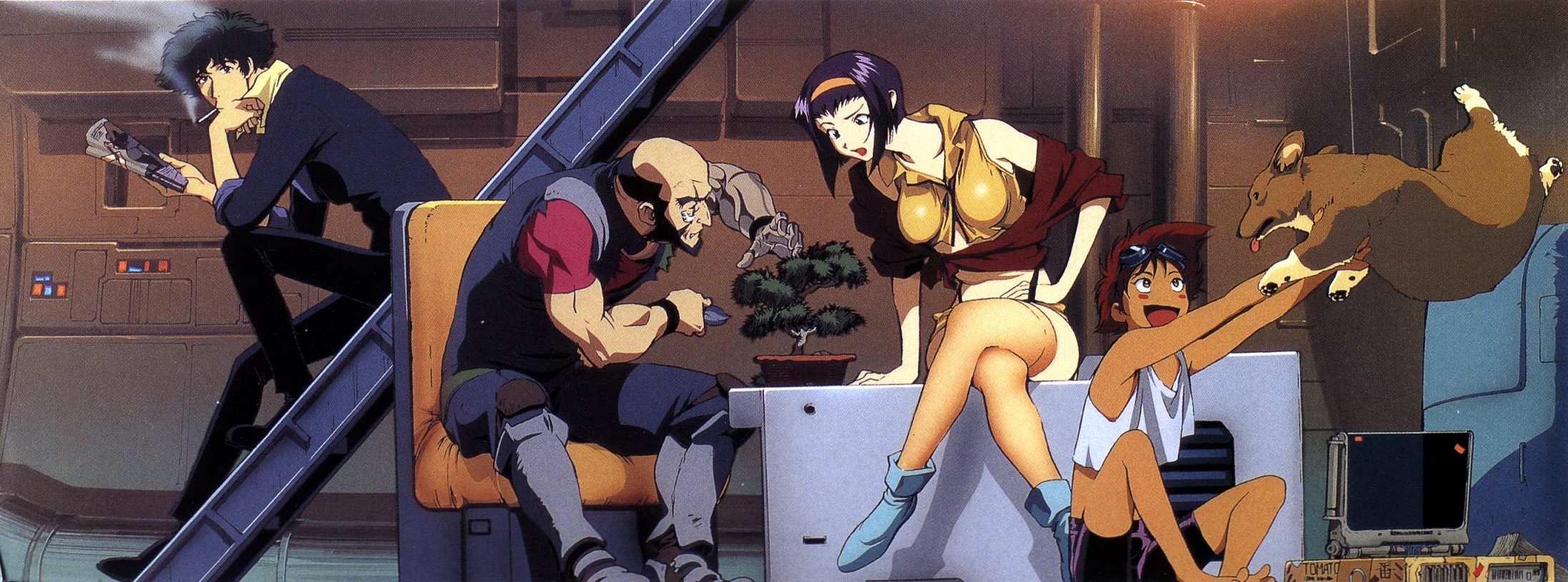

Subgenres often dictate certain elements of the art: a mecha will probably have large robots, a fantasy show will probably have elves, and an ecchi will almost certainly depict a few male nosebleeds. As a connoisseur of many different subgenres, I can say with confidence that these stereotypes are usually true. But despite their differences, most shows portray a strikingly similar core ideology. It is this underlying ideology, which persists despite visual variances, that I want to highlight. In almost every anime ever produced, the hero is a victim of circumstances outside their control. “Well, sure,” you may say. “What else could they be a victim of? Who else could be the antagonist?” And by asking these questions, you would be delving deep into the very roots of humanity itself. In fact, director Shinichiro Watanabe did this with incredible skill in Cowboy Bebop. Known for his groundbreaking work in Bebop and other shows, such as Samurai Champloo, Watanabe dared to explore the possibility that some people are their own worst enemy by depicting his protagonists as the authors of their own demise. Although it was released almost two decades ago, Bebop remains a touchstone of unorthodox thinking in the animation industry. To this day, it continues to enchant audiences across the world with its creative blend of styles. But what is it that makes the show such a masterpiece?

Throughout history, a few great thinkers have offered radical but compelling views that strike at the heart of human depravity. One of the most famous among them, Fyodor Dostoevsky, provided a succinct and shocking argument in his book titled Notes from Underground. Rather than painting humans as noble creatures, struggling against the harshness of the outside world, Dostoevsky posited that the problem lies within. “In despair,” he claimed, “there are the most intense enjoyments, especially when one is very acutely conscious of the hopelessness of one’s position.” In other words, people actually desire suffering and pain. Throughout his book, Dostoevsky goes on to suggest that even when presented with an escape from their problems, humans will often still choose to destroy their lives.

While it is doubtful that Watanabe drew inspiration directly from Dostoevsky, his directorship indicated that he had arrived at a similar conclusion. This argument was strongly conveyed in Cowboy Bebop primarily because Watanabe approached the topic gently; it was impossible to suspect his intentions until the very end of the series. Each character in the show appeared, at first, to be fighting against external chaos. As the story progressed, however, it was revealed that they were instead running from something inside them.

The truth is, Bebop is an enigma. It is whimsical and meandering, but also serious and incredibly direct. The main characters of the show consistently demonstrate a desire to flee from their past, while simultaneously failing to embrace the present or anticipate the future. Jet Black lost his family and his career, but he continually fails to grasp the closeness of the family that fate placed aboard his ship. Spike Spiegel lost his lover and prestige when he fell from a window and nearly died, yet he ignores a second chance at happiness in favor of a second chance at death. Faye Valentine lost her whole world after being cryogenically frozen, but she spends more time destroying the new world before her than she does accepting it.

Many of the supporting characters develop this narrative as well. A perfect example of this is Jet’s former girlfriend, Alisa, who ran away from him and left a pocket watch as her sole explanation. Years later, Jet returns to Ganymede and finds her living with a criminal. After being captured, Alisa finally explains why she fled so many years ago:

“…back then, you decided everything; in the end you were always right. When I was there with you I never had to do anything for myself. All I had to do was to hang onto your arm like a child without a care in the world. I wanted to live my own life; make my own decisions, even if they were terrible mistakes.”

Initially, Watanabe leads his viewers to believe that there was a tragic secret that caused Alisa to run away. However, like Jet, we are surprised to find that there was almost no reason for her behavior. Based on what we know about him, it is extremely unlikely that Jet ever did anything to hinder Alisa’s freedom; in fact, his willingness to let her go after finally finding her again supports this. The truth is, Alisa was so comfortable in the life that Jet provided, she no longer felt alive.

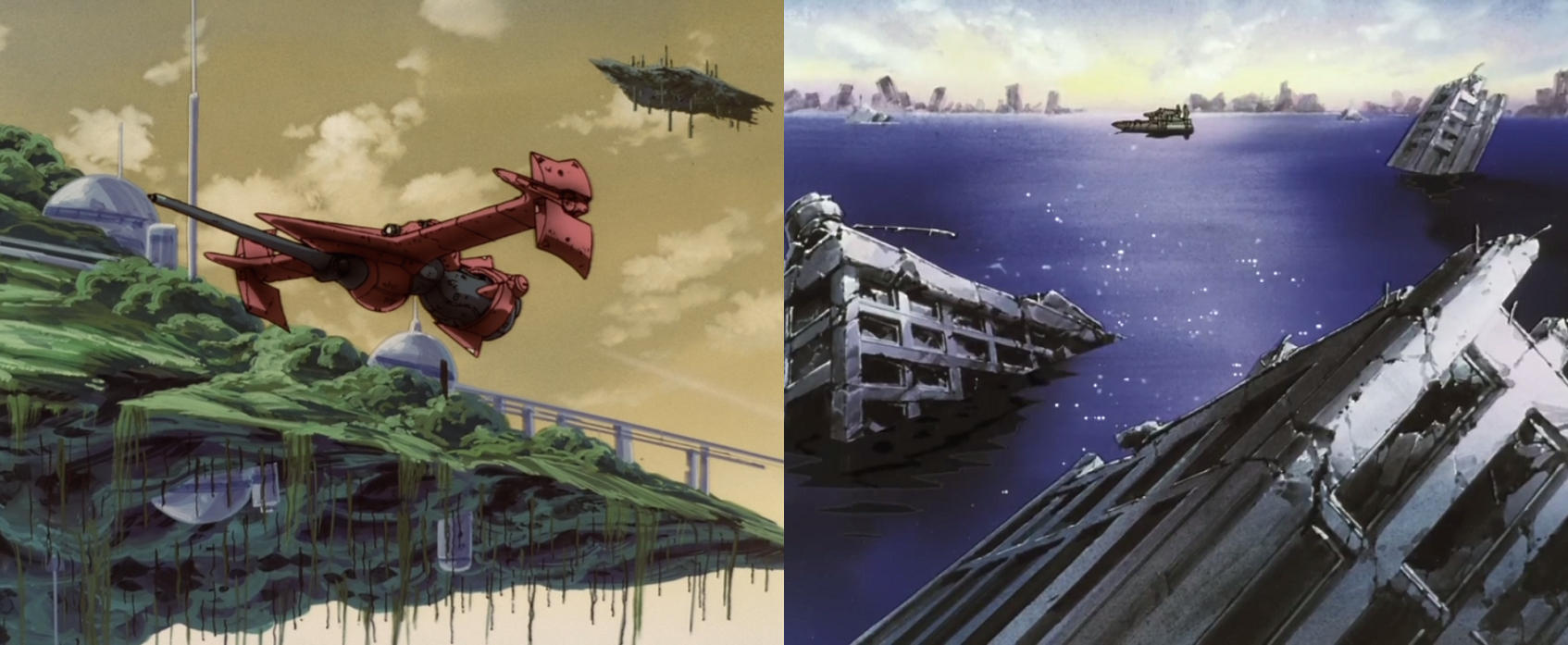

Not only do the characters present a convincing argument for the paradox of the human condition, but the music and style do as well. The futuristic universe of Cowboy Bebop is far from utopian. As a result, many sequences occur with backdrops that support their mood. This dichotomy of purpose and chaos is supported by the contrast between immense technological genius (such as the floating islands on Venus) and crippling decay (exemplified by the barren, rubble-strewn landscape of Earth). The jazz, too, shifts frequently between a frivolous, upbeat feel and a somber, melancholy tone. All of this serves to highlight the depth of the insanity.

During the last two episodes of the series, Watanabe demonstrates this madness with brutal clarity. First, Spike approaches Jet to explain that he is going to confront his archnemesis, Vicious. Understanding the implications of this, Jet tells a short story:

“A man injures his leg during a hunt. He’s in the middle of the savannah. No means to treat the wound, the leg rots and death approaches. Last minute, he’s picked up by an airplane, he looks down and sees a land of pure white below him. Glistening in the light. It’s the summit of a snowcap mountain. The mountain is Kilimanjaro. As he gazes down he feels the life flowing out of him and he thinks… that was where I was headed…”

Not understanding the point, Spike pauses a few seconds before asking, “…and?” To which Jet replies, “I hate stories like that. Men only think about their past right before death, as if they were searching frantically for proof they were alive.”

Shortly after this, Faye catches Spike as he is preparing to depart, and confronts him about it. When asked why he is leaving, he points out that ever since his accident he’s “been seeing the past in one eye, and the present in the other.” Faye then goes on to ask whether Spike plans to “throw [his] life away like it was nothing.” Delivering the final maxim of his story, Spike replies, “I’m not going there to die; I’m going to find out if I’m really alive.”

About Cowboy Bebop, Shinichirō Watanabe noted that “people see a lot of things over time. They find things they like, and these days people try to recreate what they’ve seen. That’s not what I wanted to do. I wanted to create something that had never been seen before.” To be fair, there are a number of unique things about the show; but it would be a huge mistake to gloss over the foundation of its popularity and charm. At the end of the day, Cowboy Bebop is not about heroes. It’s not about beating the odds. It’s not even about relationships. Watanabe’s true intent was to show that humans will often turn their own comedy into a tragedy simply to remind themselves that they are free, and that they were, at least for a short while, alive. And that, more than anything else, is what sets this show apart from all the rest.

Got feedback? Leave a comment here!

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.