All Everything Everywhere All at Once Images via A24

Everything Everywhere All at Once is a film that truly has everything: martial arts, Michelle Yeoh, hot dog fingers, talking racoons, Millennial child/parent angst, the works. It’s the movie equivalent of the Hyperbolic Time Chamber in Dragon Ball Z, where you live a lifetime of laughter, fear and heartbreak in the theater only to realize upon leaving that just over two hours have passed. It even managed to do respectable numbers at the box office for its weight class, a rare word-of-mouth success at a time when only superhero films and Sonic the Hedgehog are seemingly viable in theaters.

Everything Everywhere All at Once lifts gleefully from past Hollywood blockbusters, nodding to The Matrix, Avengers: Endgame, even Ratatouille. This is not a criticism. The genius of the film is its kitchen-sink approach, the way its creators mix and match high and low culture without fear or shame. Anyone can copy The Matrix. Skilled filmmakers can put together a good-enough pastiche of a Matrix fight scene. It takes someone inspired to say, “What if the Matrix pastiche involved butt plugs?” And it takes directors like Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert to reach out to the correct hard-working folks on YouTube to choreograph those fight scenes. The results beat out nearly every recent superhero film in their clarity and kineticism, while still being as eccentric as the movie’s universe calls for.

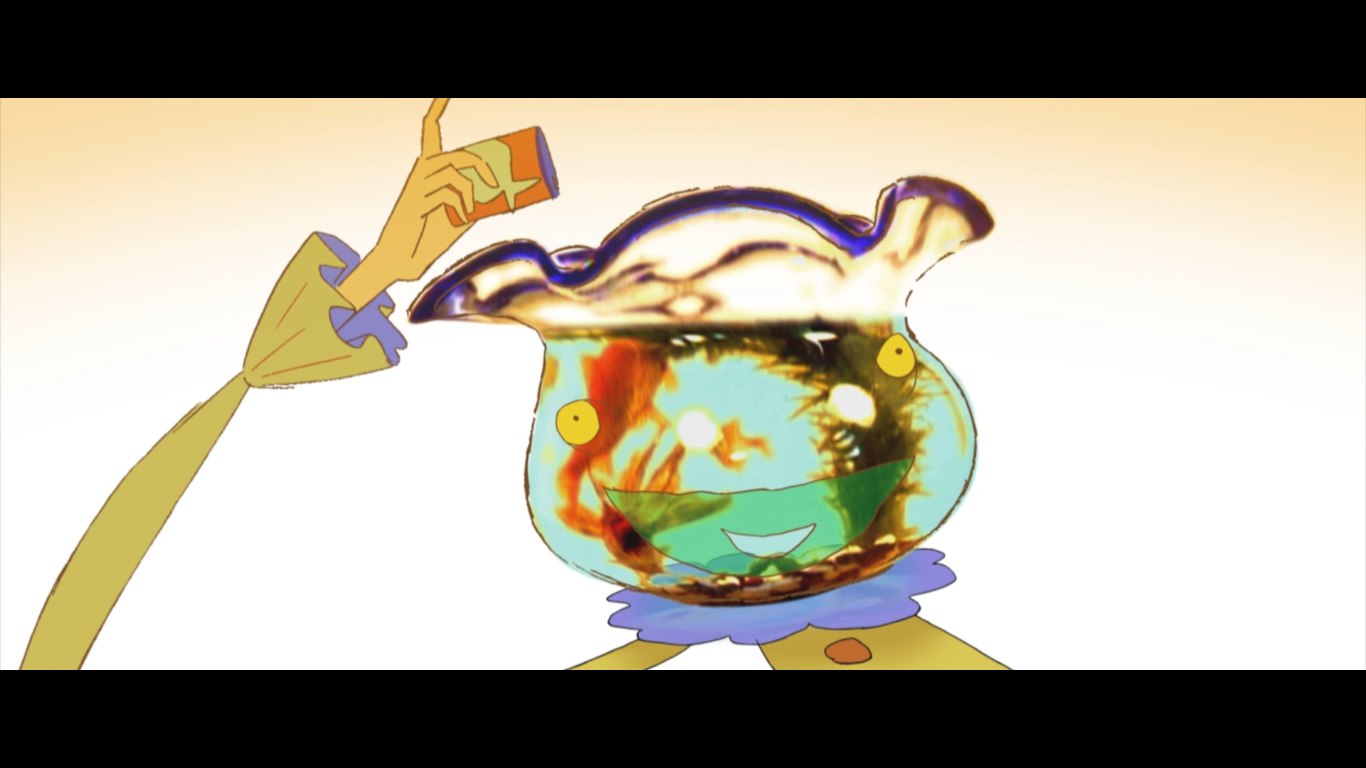

In a recent interview with Thrillist, Daniel Kwan names several films that inspired the creation of Everything Everywhere All at Once. Among reference points like Groundhog Day and Holy Motors, Kwan name-drops Mind Game, a film by anime director Masaaki Yuasa. Yuasa is best known today for his work at the studio Science Saru, directing fan-favorite series like Keep Your Hands off Eizouken! and Devilman Crybaby. But in earlier days, he was an even more experimental director, creating animation completely unlike anything else in the commercial space at the time. Mind Game is the very first film he directed, and it’s just what you’d expect from an eccentric young artist with something to prove. The animation style changes minute by minute, tone shifts incite whiplash and many scenes read as independent short films rather than part of a coherent story. It’s a confrontational and occasionally obtuse movie that loudly reminds you, again and again, of its own artifice.

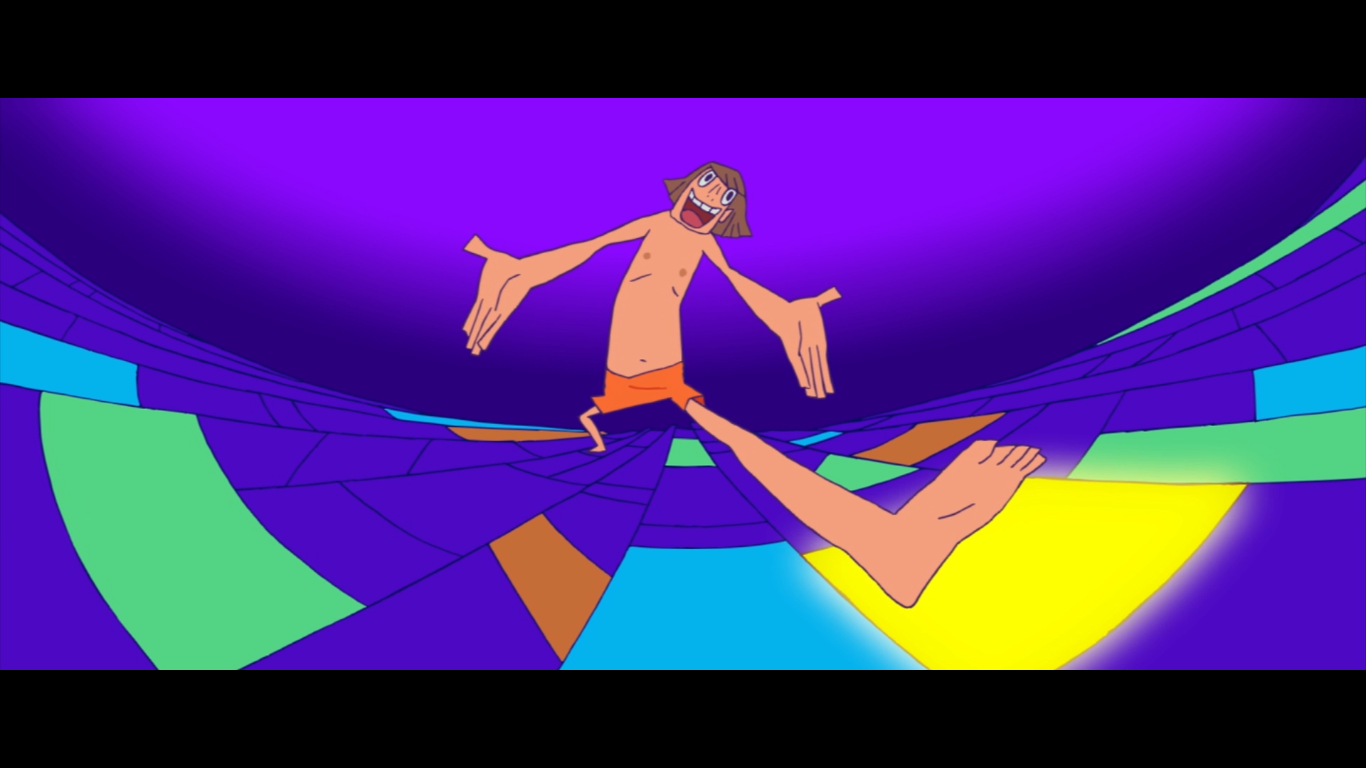

Kwan is careful to qualify his praise of the film, noting that “it doesn’t fully hold up.” But when he discusses the ending of Mind Game, he’s rapturous. “If I could do this in live-action, I will be so happy … it’s just incredible, just virtuosic editing and animation, and you’re like, what is life???” For folks who haven’t seen it: in Mind Game, the main character Nishi, his crush Myon and her sister Yan are swallowed by a whale. At the end of the film, they build a motorboat to escape, with the help of the old man they find there. Paddling against the fierce inner sea in the belly of the whale, they transcend the elements and the limitations of their bodies. The boat is smashed to pieces, but our heroes run along those pieces and then the water and then the individual atoms of the universe itself. Their all-consuming drive to live and to exist cracks the cosmos open like an egg.

RELATED: Masaaki Yuasa's INU-OH Anime Film New Trailer Announces Its Japanese Release Date of May 28

Initially, the whale’s belly appears to be the perfect place for Nishi, Myon and Yan. Nishi is finally able to move beyond his fears and anxieties once he is put into a position in which he simply has no choice otherwise. Yan cuts her hair, experiments with her self-image and becomes the artist she’s always dreamed of being. Myon becomes an accomplished swimmer, a dream she had to give up in school once puberty changed the shape of her body. Removed from the world and its demands, they are given the chance to be more of themselves, or to even be different people entirely. The varied animation styles in Mind Game speak to this same sense of infinite possibility, demonstrating how the way in which the world is perceived and expressed may change completely and utterly depending on your mood and circumstance. But Nishi, Myon and Yan eventually realize that finding liberty in the whale is not enough. Even if living in the real world means accepting mediocrity, Nishi cries, “I just want to be part of it!” In the world of Mind Game, life is both banal and marvelous, deeply meaningful in its ridiculousness.

In Everything Everywhere All at Once, the heroine Evelyn is given a similar temptation. By tapping into other versions of herself across dimensions (the martial artist and actress, the celebrity chef) she experiences how it feels to be wealthy, beautiful and successful. She finds it hard to return to being herself, a woman on the verge of losing her husband, daughter and laundromat, when she can simply be somebody else. But sooner or later, as she reaches further and further out across dimensions, Evelyn succumbs to the numbing stimulus of the multiverse. Rather than presenting new opportunities or ways of being, each new reality becomes another thing to destroy, because doing so is so much easier than having to make your own difficult choices. Evelyn is older and more experienced than Mind Game’s protagonist Nishi, yet she fears the same words that Nishi typed into his cell phone at the start of that film: “Your life is the result of your own decisions.”

The only counter for the nihilism that threatens to destroy Evelyn, and everybody she cares about, is love. Her husband Waymond tells her in a parallel universe that “in another life, I would have really liked just doing laundry and taxes with you.” Just like Nishi and his friends chose the infinite possibility and banality of everyday life over living comfortably in the whale, Evelyn accepts that the stupidity of existence is bearable so long as she has other people in her corner. Waymond may still divorce her and her daughter Joy grows further away from her, but the chance to build new connections with them, to extend a hand when they are hurting, is enough.

It’s a simple message for a movie that relies so heavily on visual experimentation and overstimulation. Some may even find it a let-down. But then, I believe that simplicity is a purposeful choice. Strip away the complex visual design and non-stop gags and the bones of the film are as clear as can be. Love each other. Be nice to your family and friends. The Daniels have always been heart-on-sleeve filmmakers. Their previous film Swiss Army Man spoke this same language of overcoming loneliness through human connection, despite beginning with the protagonist riding a farting zombie-like a jet-ski across the ocean.

RELATED: Masaaki Yuasa's INU-OH Anime Film Previews the Friendship Between the 2 Leads in New Trailer

It is here that the Daniels are most similar to Masaaki Yuasa in approach because the films and TV series Yuasa directed are all love stories. Kemonozume and Kaiba are romances. Ping Pong and Devilman Crybaby center friendships so deep that they achieve cosmic significance. The Tatami Galaxy situates its indecisive protagonist within a community he learns to love over the course of the story. Even less successful works like Japan Sinks, compromised by a punishing production schedule, find their best moments when advocating love and compassion. Whether romantic or familial, fated or doomed, every Yuasa project (whether original or adaptation) speaks the same language no matter how it is delivered. Any viewer who realizes this is equipped to brave the challenges of Mind Game and Kaiba, no matter how different they may appear to be from conventional Japanese animation.

The Daniels are not the first directors to borrow from anime. For instance, Zack Snyder borrowed a key fight scene from the climax of Birdy the Mighty Decode’s second season for Man of Steel’s action climax. But Snyder seemingly missed the tragedy of that scene, reinterpreting it in his own film as shallow bombast. The Daniels (together with fellow travelers like the Wachowskis) dug beneath the skin to find the meat of their influences. Mind Game is visual chaos not just because it looks cool, but to demonstrate how its hero Nishi experiences life. Similarly, Everything Everywhere All at Once utilizes editing, visual gags and the strength of its lead performances to convey to the audience the wonder and terror of being alive in 2022.

The line between animation and blockbuster films has been blurring in recent years. The Marvel films, for instance, rely heavily on CG special effects and pre-visualization to keep pace with their demanding schedule. Peter Ramsey, of Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse fame, is set to direct Star Wars: Ahsoka, an upcoming live-action TV series. Meanwhile, animated films themselves remain consigned to critical obscurity in the United States, save for Disney or Pixar productions. The Daniels don’t care about respectability; they made a movie where Daniel Radcliffe plays a farting corpse after all. Rather than hide its debt to animation, Everything Everywhere All at Once wears it as a token of love. I hope that one day, other filmmakers will be brave enough to follow suit.

Have you seen Everything Everywhere All at Once yet, or are you waiting for it to make the jump to streaming? What is your favorite work directed by Masaaki Yuasa? What would you do if you were swallowed by a big whale? Let us know in the comments!

Adam W is a Features Writer at Crunchyroll. When he isn't thinking about rocks, he sporadically contributes with a loose coalition of friends to a blog called Isn't it Electrifying? You can find him on Twitter at: @wendeego

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.